Written by: Darko Vlahović

Photos: Tomislav Marić

…

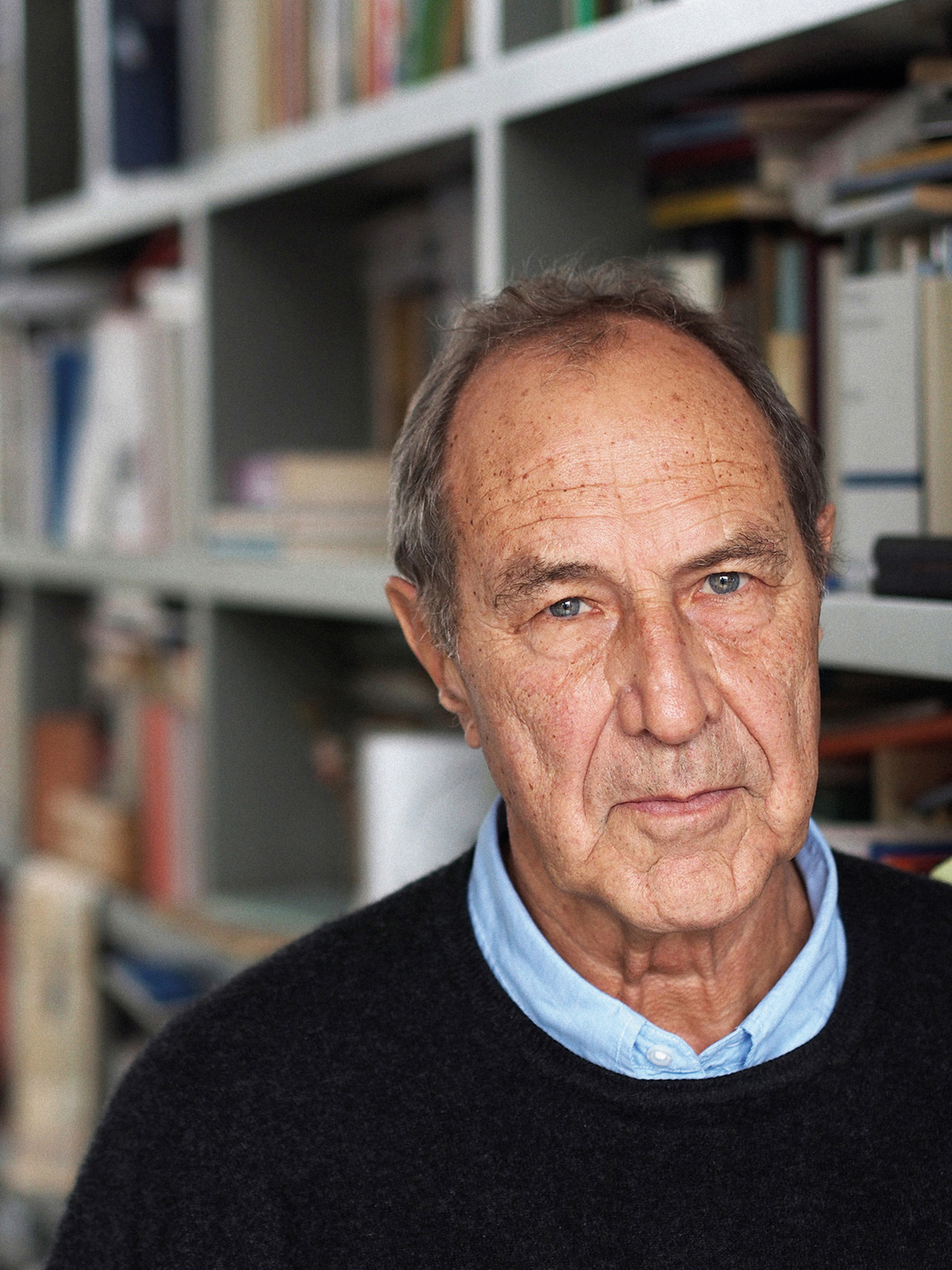

Doc. dr. sc.. Krešimir Gršić is one of Croatia’s leading experts in the field of otorhinolaryngology and plastic surgery of the head and neck. Born in 1977 in Zagreb, he began his medical journey at the University of Zagreb’s School of Medicine, graduating in 2001. Today, with a wealth of clinical and scientific experience, he serves as the Head of the Department of Head and Neck Surgery at University Hospital Center Zagreb.

In addition, he is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Medicine and at Libertas International University, where he actively participates in educating future doctors. During his career, Gršić pursued further training abroad, including a study stay at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, where he became acquainted with modern oncology protocols for head and neck tumour surgery. He is the author of numerous scientific papers, a collaborator on international research projects, and a specialist in plastic-reconstructive surgical procedures and thyroid surgery.

Beyond medicine, he is also dedicated to humanitarian work: as president of the Zagreb League Against Cancer, he organizes many educational and humanitarian initiatives for oncology patients and their families. In this interview, Gršić shares the connections between medicine and art, why the golden ratio is important in surgery, how his artistic family is linked to his private clinic QMC, and what his future plans are.

What is the connection between art—painting and sculpture—and medicine, particularly surgery? We consider the golden ratio to be the foundation of aesthetics in art and architecture. How did you recognize it as relevant in surgery?

Art and medicine, especially surgery, share a surprising number of similarities. Both disciplines are highly demanding and require years of education and the acquisition of specific knowledge and skills. In surgery, as in art, there is a strict methodology that must be followed—the path from point A to point B must be precisely defined and executed with almost military discipline.

Just as a painter must master the composition of shapes and colours before developing their own artistic expression, a surgeon must first master the basic patterns before gaining freedom in their work. This brings us to the concept of the golden ratio, which is not only the foundation of aesthetics in art and architecture but also a key principle that can be applied to surgery. The golden ratio defines the proportions between elements—what’s in the foreground and what’s in the background, what is above and what is below, which colours complement each other. In surgery, this concept can be seen in the rules about which sutures to use, how to approach a specific structure, when and how to do so, how to perform an operation with minimal damage and maximum benefit for the patient.

We might put it this way: the golden ratio is the form, and our personality and experience determine how we will express that golden ratio—whether through sculpture and painting, or through medicine.

Have there been specific cases in your practice where your understanding of the golden ratio helped you achieve better results? Are mathematical principles useful tools in achieving aesthetic balance, or are they more of a theoretical concept?

An image that dominates medicine—and is one of the most famous examples of applying mathematical proportions to the human body—is Leonardo’s illustration of the Vitruvian Man. In that drawing, Leonardo da Vinci precisely described how every part of the body can be mathematically related to others.

The width of a finger, for example, corresponds to one-seventh of its length, and similar proportions can be found throughout anatomy. Almost every feature of the human head can be analysed using the golden ratio. For instance, the lower lip should be approximately 1.6 times larger than the upper lip, and there’s also a precise mathematical relationship between the width and height of the nose. But one of the most interesting and complex shapes on the human body is undoubtedly the ear. Its form resembles a seashell, making it one of the most original examples of the golden ratio in nature. This mathematical pattern is found in many natural structures—from spiral galaxies to floral patterns—and in humans, it is most clearly visible in the shape of the ear.

Interestingly, the developmental stage of a newborn is assessed, among other things, by the shape and formation of the ear, which further confirms its importance in human anatomy. Despite all technological advances, modern surgery has still not developed a method to faithfully reconstruct the ear—its complexity and precise mathematical proportions make it one of the greatest challenges in reconstructive surgery.

Finally, the shape of the entire human head—the position of the eyes, forehead, pupils—can be analysed using the golden ratio. When a computer tries to evaluate facial beauty, it is essentially doing nothing more than mathematically analysing the key points of proportion and how closely they align with the rules of the golden ratio. Our perception of beauty seems to be deeply rooted in natural laws that evolved over time. We intuitively recognize beauty through perfect mathematical proportions that are all around us.

To what extent does aesthetic surgery follow contemporary beauty standards, and to what extent does it adhere to universal proportions? Are current trends moving away from “natural” harmony and beauty?

I think we could all pretty easily agree on who we find beautiful and attractive. We might say that’s classical beauty—the kind that was admired a hundred years ago, is admired today, and will likely still be admired a hundred years from now. That’s the kind of beauty we recognize through the golden ratio.

However, social fashions, trends, and marketing have a huge influence, they impose new standards of beauty. It’s no longer enough to drink a regular coffee with milk—each month, a new flavour must appear to stay trendy. In a similar way, marketing today shapes, changes, and even destroys aesthetic standards that held for centuries. For economic reasons, new trends are often pushed that don’t necessarily align with the natural ideals of beauty.

For example, one of the most common procedures in aesthetic surgery today is lip augmentation. It’s true that lips lose volume with age, but instead of restoring them naturally, we increasingly follow trends that dictate specific shapes—Russian lips, Korean lips, French lips… Younger generations, who are especially susceptible to marketing influences, have begun altering their bodies beyond the proportions of the golden ratio, chasing after fleeting fashion trends.

The same thing is happening with noses. In the past, a Greek or Roman nose gave someone character. Today, people want small, harmonious “Barbie” noses with a pronounced tip, without thinking about how those procedures will look in 5, 10, or 20 years.

If we’re talking about the golden ratio and art, it’s important to emphasize that once an artwork is completed, it remains unchanged—Mona Lisa has looked the same for centuries. But when a surgeon operates on a human being, it’s not a final structure. The human face changes over time, as do all its components. A youthful face and body have the shape of an upward-facing triangle, but over time, due to gravity and changes in tissues and bones, that triangle flips downward.

That’s the key difference between art and aesthetic procedures—an artwork remains unchanged, while the human body continuously evolves under the influence of time and biological processes. Therefore, when making decisions about aesthetic interventions, it’s important to keep in mind the long-term consequences and the natural laws of the human body.

How did your medical career even begin? What attracted you to medicine, and specifically to head and neck surgery? Was it a conscious choice or a matter of circumstance?

Even before I turned 18, I knew I wanted to become a doctor, because I was deeply interested in it and understood that it’s a calling in which a person can fully realize themselves. I was ready for lifelong learning and growth. For me, medicine was never the end goal, but rather a beginning—a dynamic field that demands daily, constant dedication. The ongoing learning and development make it extremely challenging and fascinating.

Surgery, in addition, is a technical discipline where top results are only possible after years of hard work and refinement. That suited me perfectly. I was lucky to learn from excellent mentors who guided and inspired me. Thanks to them, my passion for medicine only grew. Medicine is not just my job—it’s my calling. I’ll never stop working in this field because I don’t see it as a path with an end, but as a continuous journey and an endless opportunity to learn and progress.

Your career path has been very specific and focused. Can you briefly describe the key turning points in your career? Which mentors or professors had the greatest influence on you and helped shape you as a professional?

I would say I was in the right place at the right time, which rarely happens in life. You don’t often get to choose where you’ll end up, but I was lucky. One person I must mention is Primarius Danijel Došen. He welcomed me and said the following: “I’ll take you. Work here for six months, volunteer. You’ll get to know us, and we’ll get to know you. If you like it, you can stay, and if we like you—you can work here.”

In a way, he gave me my chance, and he became the key person and guide in my professional life, especially when it came to education. He had a wonderful trait—he didn’t hold young people back. Surgery and medicine are like open fields: how much you harvest and how deeply you go depends entirely on you.

Unfortunately, today we often come across people who try to slow down their younger colleagues, who don’t want to support them. Primarius Došen was the exact opposite—he pushed us forward, encouraged our growth, and never held us back. He gave us freedom for our own projects and would say: “Carry them out, and I’ll support you. If you need protection, I’ll stand behind you. I’ll push you as far as I can until you’re ready to fly on your own.”

Today, we lack exactly those kinds of people—those with vision, who recognize young talent, encourage them to go beyond their limits, but also provide them with structure and direction. That’s what true mentorship is. His rule was simple: never do harm to others, but always guide them forward. He worked at the Oncology Clinic and was my first mentor. With him, I learned all the fundamental things—perhaps not so much about surgery as about having a broad perspective on the world. He was an incredibly versatile man.

He adored art; every few months, he would go to Milan, to La Scala, or to Florence. He would buy the most expensive tickets, sit in the front row, and enjoy the opera. On the other hand, he never publicly promoted what he did or how he did it. He didn’t want to be in the spotlight and never gave in to modern trends of self-promotion. He simply enjoyed it—in art on one side, and in surgery on the other.

To what extent do patients today come in with unrealistic expectations, and how do you handle such situations? Where do you draw the line between the need for a medical procedure and the mere desire for aesthetic improvement?

Let me go back a bit and touch on some additional context. For the first 10 to 15 years of my career, I worked exclusively in oncological surgery, more precisely in plastic-reconstructive surgery. We performed major operations—removing half of the tongue, the jaw, the neck—truly demanding procedures. After that, we used various reconstruction methods: transplanting tissue from the hands, legs, intestines, or abdomen to restore, first and foremost, function to the patient, and then also aesthetics.

Plastic-reconstructive surgery deals with bones, muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and other deep tissues. On the other hand, aesthetic surgery primarily focuses on improving appearance—skin, muscles, nose projection, and other superficial elements of the face and body. In other words, plastic-reconstructive surgery includes aesthetic surgery, while aesthetic surgery is limited to surface structures.

From that perspective, I’m always very realistic in assessing what can be achieved through surgery, and I take an extremely conservative approach. My guiding star is the golden ratio: I clearly understand the limits of each operation, and we must never prioritize aesthetics over function. Unfortunately, people often choose appearance over functionality. They want a smaller, upturned nose without thinking about its primary function—breathing. When performing aesthetic procedures, we must remain within the framework of function. Aesthetics must never compromise health.

The line between ethical and unethical conduct can easily be crossed, especially when financial interests are involved. Patients come with certain requests, and sometimes they must be turned down—not just for ethical reasons, but for their own good. Because if we operated at any cost, we would actually be doing them more harm.

Aesthetic surgery must never lose its medical foundation. We must not turn people into caricatures. We cannot inject 10 ml of filler into someone’s face or apply Botox to the extent that all facial expression is lost. We must always keep the golden ratio in mind, stick to a conservative approach, and prioritize function. Aesthetics should only be the finishing touch, never the primary goal.

You mentioned that thyroid surgeries are now part of your routine, but these are actually high-risk procedures…

In terms of numbers, I’ve performed between four and five thousand thyroid surgeries so far. My youngest patient was two or three years old, and the oldest was 99. Interestingly, thyroid surgery was banned a hundred years ago because it was considered extremely complex. The thyroid is the most densely vascularized organ in the body, and when surgeries first began, the mortality rate due to bleeding was as high as 50%. Today, it’s considered the pinnacle of surgical skill. American medicine, which developed intensively about a century ago, owes much of its advancement to thyroid surgery.

What makes this surgery particularly challenging? It’s a very small organ located low in the neck, in an area where many vital structures converge. Its anatomy is highly unstable and variable. During surgery, it’s necessary to completely remove the thyroid while preserving the trachea, the nerves responsible for speech, and the parathyroid glands that regulate calcium levels in the body. All of these structures are only one to three millimetres in size, which makes the surgery a true surgical feat. The key to a successful operation is precision—removing the carcinoma while preserving all vital structures so the patient can leave the hospital within 24 hours.

Every surgery is a new challenge, a new “blank sheet of paper” the surgeon must carefully write on. The approach—top-down, bottom-up, from the left or the right—is always dictated by the specific case, because no two surgeries are the same.

One of your areas of expertise is oncology, specifically tumours in the head and neck region. Is there any hope of defeating cancer in the foreseeable future? Will the survival rate of oncology patients ever reach 100%?

Realistically, our chances are close to zero. Scientists have calculated that, even under the best conditions, a human can live up to 120 to 130 years. Our organs—like the pancreas, liver, and others—have a limited lifespan and inevitably deteriorate over time. It’s believed that about ten new tumours form in the human body every day, but the immune system usually manages to eliminate them. However, the development of cancer is influenced by many factors—food, sunlight, chemicals, smoking, alcohol, and our genetics. In a way, cancer is an incredibly “intelligent” disease. It adapts to the body, uses mimicry mechanisms, evades the immune system, and develops resistance to treatments like chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy.

Today, life expectancy is significantly longer than a hundred years ago, when people lived to around 40 and mostly died from infectious diseases. Now, most people die from heart disease and cancer. The longer we live, the greater the chance that a small, unnoticed tumour will eventually spiral out of control. Unfortunately, there’s no chance we’ll ever find a cure that will completely eradicate cancer. The more we try to suppress it with therapy, the faster it adapts and slips out of our grasp. At best, we’ll be able to manage it and prolong life into old age, but we will never completely defeat it.

What we can do for ourselves is adopt healthy lifestyle habits. While we can’t change our genetics, we can influence our diet, physical activity, and overall lifestyle, which are the best forms of prevention. The statistics are clear—some cancers are dependent on genetics and diet, some are not, and some we treat more successfully than others. But the ultimate truth remains the same: we will never fully defeat cancer.

Your clinic, the Quality Medical Center (QMC), is a family project. How did the idea of founding your own clinic come about?

I would never have started this project if it weren’t for the COVID pandemic. Unfortunately, that’s when I realized how the entire healthcare system was collapsing. On the one hand, it was a serious problem, but on the other, there comes a point in life when you want to invest in yourself, your education, and professional development. I saw how slow the healthcare system was—decision-making and implementation processes, as well as treatment capabilities, had become extremely complex, limited, and overwhelmed by bureaucracy.

At that moment, I decided I had enough energy and strength to launch my own project—a place where I could offer patients the best of myself and my colleagues, at the highest professional level. At the Quality Medical Centre, only doctors with at least 10 to 15 years of specialist experience work, and they routinely perform even the most demanding procedures. Our goal is to provide top-tier medical care in optimal time, without unnecessary delays.

What services does QMC provide?

We specialize in head and neck surgery, including tumour operations, thyroid and salivary gland surgeries. Additionally, we perform aesthetic surgeries—nose, lip, and facial corrections, as well as breast surgery. We also offer high-level care to patients with diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

Our focus is on providing high-quality care from leading experts—quickly, effectively, and with the best possible outcomes.

What role does art play in the clinic’s interior design?

Most people who come here notice the same thing—one of the most common comments is: “This looks like a man’s technical clinic.” The space is absolutely white, so bright and filled with light that it’s almost hard to look around normally. But that’s intentional—technical and sterile, just as a medical space should be.

However, there is one detail that adds warmth to that sterile whiteness: original artworks from my family. The clinic’s walls are adorned with graphics and artworks by my wife, Jana Žiljak Gršić, a well-known designer who created numerous visual identities, including the logos for KBC Zagreb and the Dr. Fran Mihaljević Clinic. Jana is also the dean of the Polytechnic of Zagreb.

Artistic talent continues in her family through her mother, Nada Žiljak, an academic painter who has been active in art for over 50 years and has held more than 50 solo exhibitions. One of her most remarkable achievements was a piece she created for the Emperor of Japan—an

extraordinary honour. Nada is known for her distinctive style, particularly for her infrared painting technique, which is internationally

recognized.

This means that within each image, visible to the naked eye, there are hidden romantic messages—a concept she developed at the suggestion of her husband, Vilko Žiljak. He is known to the public as one of the designers of the Croatian kuna, which he created with Šutej. But his legacy goes far beyond that—he is one of the pioneers of computer graphics, not only in Croatia but globally. As early as the 1970s, his first digital artworks were displayed at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York as groundbreaking achievements.

Finally, we come to the artist who, in my opinion, might be the most powerful of them all—Nada’s father, Albert Kinert. His works are unique, full of vitality and subtle sensuality, and it’s precisely that energy that brings soul into this sterile space. His paintings create a strong contrast to the clinic’s cold whiteness, introducing warmth, dynamism, and artistic passion into an otherwise purely technical environment.

How do patients react to that?

It’s actually one of the elements we use to help relax our patients. When they see the artwork, almost everyone stops and becomes interested—they read Kinert’s poetry, observe the pieces. It’s especially interesting because we don’t keep the usual magazines in the clinic, but rather art catalogues. I believe it’s much more pleasant to look at paintings or browse through art books while waiting for a diagnosis or preparing for surgery than reading disposable magazines that are forgotten the next day. The reactions are great, and the idea has proven to be a real success.

The artworks truly enrich the clinic. Whenever we perform surgery, they serve as a reminder of the importance of the golden ratio—of staying true to the rules, staying true to ourselves, and not succumbing solely to marketing influences. Within that golden ratio, we refine our procedures, elevate our surgery, and remain faithful to excellence.

How do you balance your professional and personal life, given that surgery demands total dedication? Do you even have time to focus on yourself?

I like to say I live medicine 25 hours a day, seven days a week. For me, there is no boundary between private life and work—it’s all intertwined, all part of the same path. My life is organized so that we’re constantly working on new projects, and that’s what sets us apart from others. We never look backward, we don’t tear others down—we build ourselves, and by doing so, help others. That ultimately makes life easier.

Photography has always fascinated me, especially digital photography. I’ve had several digital cameras for over 20 years, and I’ve always preferred photography over video. Why? Because photography captures and freezes a moment, turning it into a work of art.

Photography has brought me two important things in life. First: in medicine, I carry a camera daily and document various procedures, creating a valuable collection of educational material for students. Second: in my private life, it allows me to observe people around me and capture precious moments with my family. That’s something that fulfils me.

What are your future plans—professionally and personally? Are there any projects you’re currently working on that are especially important to you?

Our future plans are very exciting and mostly focused on scientific research. We’re particularly interested in connecting art and medicine through innovative projects. Right now, we’re working on a fascinating study in collaboration with director and photographer Dinka Radonić. Through her doctoral research, we’re exploring various light spectrums, including infrared and other parts of the spectrum invisible to the naked eye.

Our goal is to study the tissues I operate on and, through specific light wavelengths, discover new diagnostic possibilities. Specifically, we’re exploring ways to detect cancer cells and changes in thyroid tissue using certain spectral analyses. So far, we’ve made some very interesting discoveries that could have a major impact on practical medicine. This interdisciplinary project is completely innovative and opens new areas of research that we’re incredibly excited about.

The second major project I’m working on is focused on student education. In recent years, I’ve been recording video materials in 3D to enhance teaching and give students better insight into surgical procedures. At first, we modified available cameras, mounted them on helmets, and recorded surgeries from the surgeon’s perspective. These 3D models allow students to learn surgical techniques directly, from the surgeon’s-eye view. This innovative approach has gained international recognition, and we’ve won several prestigious awards for it. In fact, our video materials have become official educational content for European medical student associations and are now used as standard training tools across Europe.