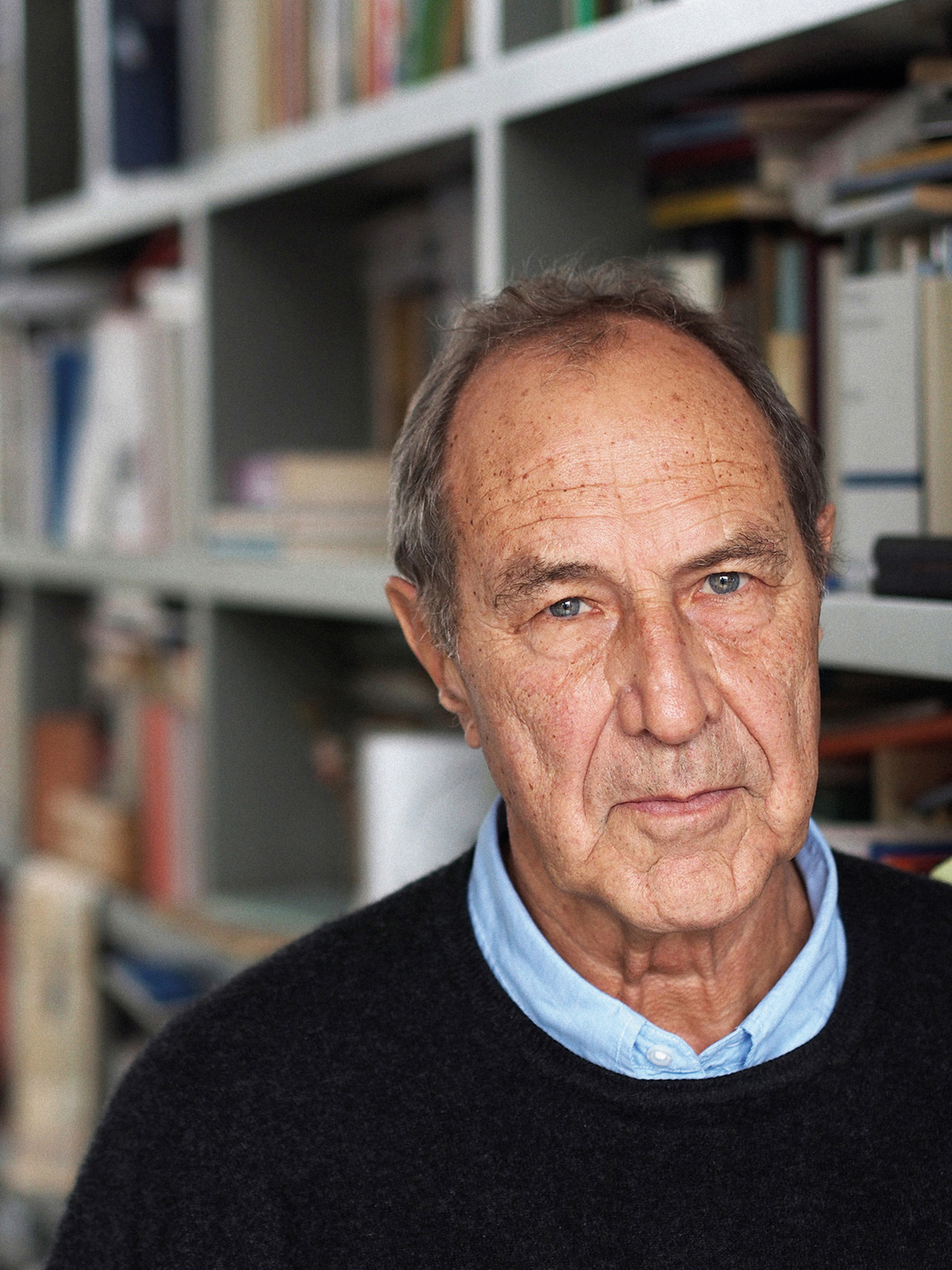

Written by: Darko Vlahović

Photos: Vojtech Veskrna & Studio Wim Delvoye

…

The aim of art is not to portray the outward appearance of things, but their inner meaning. This famous thought by Aristotle perfectly describes the oeuvre of Wim Delvoye (Wervik, 1965), a Belgian artist whose works are simultaneously provocative, witty, and technically flawless.

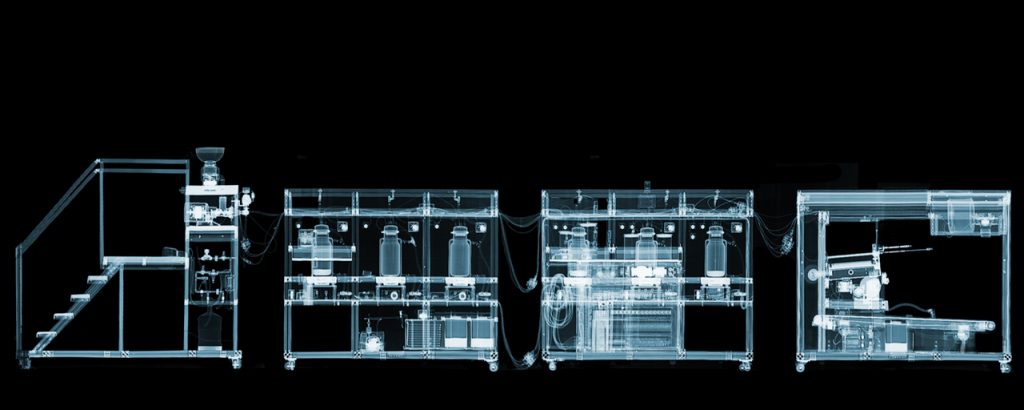

His art brings together opposites – high aesthetics and industrial processes, Gothic poetics and digital precision, biology and technology. From tattooed live pigs to the iconic Cloaca, a machine that replicates human digestion, Delvoye never stops pushing the boundaries of art and ethics.

In this interview, we discover what inspires him, how he sees the future of art, and why he has always been drawn to the fusion of tradition and innovation.

You grew up in Wervik, a small Belgian town right on the border with France. What steered you toward art?

The fact that I wasn’t particularly good at math and the exact sciences influenced my choice of studies—I was looking for a field that didn’t require them. That was probably one of the key reasons I leaned toward art. But later, it turned out to be a point of no return.

I belonged to a generation in which compulsory military service was still in place. One way to avoid the draft was to simulate mental instability. Which I did. However, that came with serious consequences. When you’d later look for a job, employers would ask if you served in the military. If you answered “no,” the next question would be, “why not?” And the answer “because I was declared mentally unfit” meant you weren’t getting the job. So, by the age of 20 or 21, it was already clear to me that I didn’t have many options—I had to find a way outside those limitations.

Today, with compulsory military service no longer in effect, that situation seems distant, but in my time, it was crucial. I think about it often because I hear more and more proposals to reintroduce the draft, which brings me back to the period when I first realized how unjust that system was. You study hard, graduate, and then you’re forced to spend a year in the army, often doing meaningless tasks, while your female classmates are spared. I thought the law was sexist—men had to serve, women didn’t. If you claimed conscientious objection, the punishment was even greater: instead of one, you had to spend two years working in a library or another state institution. In other words, you were punished for having a conscience and refusing to carry weapons.

I wanted to avoid both math and the military—those were the two key reasons I ended up in art school. In the end, in a way, I didn’t consciously choose art—I was forced down that path.

Can you tell us a bit about your student days at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent and how they shaped your artistic journey?

At the Royal Academy, I enrolled in painting with simple expectations—I just wanted to learn how to paint. What was also key was that I had incredibly relaxed parents who always supported me. Sometimes, when I’d get pragmatic and start thinking that maybe art wasn’t the safest future, they would encourage me and bring me back to it. They’d say, “But you love studying this!” I’d reply, “Yes, but I could study something boring, think about a stable future.” But they always insisted, “No, no, something boring would make you unhappy.” Thanks to them, I had the freedom to choose what genuinely interested me.

During my studies, I realized how important their support had been. Many of my classmates had to make compromises because their parents would say, “At least study photography, maybe that’ll help you get a job.” In retrospect, that sounds ironic: many of them are unemployed today, because for the past 20 years, everyone has carried a camera in their pocket via their phone. Photography, at least as a classical profession, has no future.

The parents of those classmates of mine tried to be smart, but the future is impossible to predict in all its details—especially when it comes to a child’s life path. My parents didn’t know what awaited me either, but they took a big risk by encouraging me.

So, you began studying painting—how did you end up in conceptual art?

I started studying painting with a classical approach, but I quickly became interested in three-dimensional objects. I began painting on everyday items, exploring space and the third dimension. During my studies, I became more and more drawn to experimenting with the medium and expanding the boundaries of painting. Painting is, by the way, a very “grateful” discipline—it’s not too expensive, you don’t need much space, and the market for paintings is far larger than that for conceptual art. It would have been great if I had stayed a classical painter, but I was always interested in something more.

Slowly, I became consumed by working in three dimensions, until, after many years, I realized I was actually a sculptor. I’m very serious and critical when it comes to my ideas. When I come up with one, I don’t realize it right away—I store it like wine aging in a cellar, letting it improve over time. Ideas also need time to mature. I always expect a lot from painting, but it’s not easy to reach the level I aim for.

I admire the old masters—the way they painted eyes, hands, that level of skill fascinates me. But if I were to compete with the past, with the old masters, it would paralyze me and stop me from doing what I want. That’s why I don’t limit myself to one technique or one medium—every technique is valuable, every craft has its own power.

Still, never say never—who knows where art will take me next…

How do you choose themes for your projects? Is there an intuitive or research-based process behind it? Would you say your artistic process is more spontaneous or a long-term, thought-out experiment?

I always look for some kind of social dimension. When I get an idea, I test it on the people around me, observe their reactions, remember them, and try to understand why each person responded a certain way. But I always stay open to new ideas. Some of my colleagues get stuck in their own artistic dead ends because they cling to their creeds more than they search for new ideas. Over time, their ideas become dogma, and they stay trapped in their own niche. This especially applies to artists who were active before my time—say, the generation from the 1960s. Many of them created something recognizable and remained loyal to it their entire lives.

A great example of that is On Kawara—the more he created, the better he became, but he kept doing the same thing for the rest of his life. That was a generation where an idea turned into commitment, and commitment became a credo. That kind of approach was also marketable—this kind of art was instantly recognizable. You could say from afar, “That’s On Kawara!” and immediately sound like a connoisseur of contemporary art. Those artists never disappointed; they always made the same things, almost like machines.

Another example of that approach is Roman Opałka. He spent his whole life painting numbers and self-portraits as he aged. But my generation started playing with that concept and commenting on it. We asked ourselves—why would someone commit to the same thing their entire career? That’s boring. Why stop being creative? Sure, doing the same thing every day can be great, but at the same time, it’s incredibly monotonous—as if you’re an artist working a 9-to-5 job.

My generation didn’t commit to anything: we tried to stay creative.

Which artists or movements have had the greatest influence on your work, and in what way?

It could be anyone. If you’re not committed to one aesthetic, your influences can change every week. But if you’re, for example, a lifelong Cubist, you’ll probably say Cézanne had the biggest impact on you.

I don’t have one specific person who constantly inspires me. I usually look at artists who might give some kind of legitimacy to what I’m doing. Let me explain—maybe I come up with an idea that resembles something someone in the past already did. In that case, that artist lends legitimacy to what I’m doing, because without those lines of ancestry, art often can’t exist. Experimental art relies heavily on history, on artistic predecessors, on referencing earlier artists. For example, today’s artists working with ready-mades automatically reference Duchamp and have to define their position in relation to him and the long line of their predecessors.

With me, it’s not that straightforward—every one of my works draws inspiration from a different person. Among dead artists, I really like Piero Manzoni, the Italian artist from the 1950s and ’60s. He’s far enough in the past to give legitimacy to what I’m doing, but he can still inspire me. But I also like looking at works by artists like Picasso—not because they have a direct influence on me, but because they fascinate me.

Every month I’m obsessed with a new artist. Recently, for example, I was fixated on Augustus Pugin, a 19th-century architect who designed Big Ben. Two months ago, I found him incredibly interesting, and then I moved on to something else. Now it’s someone new again—it might even be, for example, Hitchcock. In fact, inspiration doesn’t have to come from an artist at all. It could just as easily be a filmmaker or someone I previously had no interest in, but suddenly I discover something in them that inspires me.

Anything that happens in the world can be a source of inspiration—something from popular media, pop culture, or even something that doesn’t seem like art at first glance.

How do you define the boundary between provocation and art, especially when your works evoke strong reactions from the audience? Are you even interested in how the audience reacts? Is provocation a goal or a byproduct of your artistic expression?

Today, we’re surrounded by millions of images—we’re swimming in an ocean of visual information. When I was a young artist, my camera had film with only 36 frames. Every photo had to be thought through because I had to carefully choose what was worth capturing. Today, that only really applies to tattoos—the body is a limited canvas, every line is painful, so people think a hundred times before tattooing something permanently. Yet ironically, they still often choose something meaningless. (laughs)

Art, like tattoos, tries to resist impermanence. Artists hope their work will outlive them. But in a world oversaturated with images, the audience has become immune to visual stimuli. We’re exposed to thousands of new images every second—how can we even stop and really look at anything anymore? That’s why an artist must be extremely clever to grab attention, regardless of the medium. They have to be like a virus that breaks through filters and stays in the viewer’s eye and mind.

Sometimes, that means shocking people—but not for the sake of provocation, rather to break through the visual chaos. But what is truly shocking nowadays? When you place a provocative artwork in a museum, people react immediately—but it’s nothing compared to what we see daily: scenes from Gaza, Yemen, natural disasters, hurricanes, wars. In that context, art can hardly be genuinely shocking.

We live in an era where art competes not only with the great masters of the past, but also with social media, TikTok, Instagram—an overwhelming flood of images that engulfs us every day. I’m part of a generation that struggles not just with tradition, but with the digital age and its endless visual bombardment. I’m grateful to be able to create in a time that allows it. In another historical period, I’d probably have been burned at the stake for my art.

What inspired you to create Cloaca, the machine that replicates human digestion? It’s probably your most well-known work. What kind of audience reaction did you expect?

I was surprised by the reactions. You think you’re clever, that you can predict everything—but you can’t. Everyone is shaped by a certain culture, and that always becomes apparent. In Belgium, some people—predictably—claimed it wasn’t art. But to my surprise, most accepted the installation. I had expected more criticism. In New York, it was a big success, but there, people were concerned about bacteria—something that never even crossed anyone’s mind in Belgium. I guess Belgians are less sensitive to that kind of thing? (laughs)

In Germany, the focus was on ethics—I heard comments like: “This artist is wasting food while children are dying of hunger.” But art always consumes resources, whether it’s paint, marble, or bronze. That moral concern struck me as very Protestant. In Protestant culture, wasting food is considered a sin. I didn’t expect that kind of reaction…

In Austria, the story was completely different—they immediately started talking about Freud, psychoanalysis, childhood, mothers, and feces. I liked that, but I couldn’t have predicted such a psychoanalytical enthusiasm in response to the installation. That piece really showed me how each country has its own personality and interprets the same art in completely different ways.

Your practice of tattooing live pigs sparked controversy. How do you respond to criticisms about the ethics of that project? Did it also provoke different reactions in different countries?

The reactions varied depending on the time period. In the 1990s, animal rights weren’t a serious topic, so tattooing pigs didn’t cause much controversy. But much later, in the Netherlands, I had to defend myself—I even showed video footage to prove that the animals weren’t suffering.

It’s not about geography—it’s about time. In the past eight or nine years, the mentality has changed. Young people have become less tolerant, and social media has triggered a wave of moral condemnation. Online, it’s easy to be intolerant. You can call yourself Mickey Mouse and attack whoever you want, without consequences. When I saw how many people were against me, I even began to question myself… But the truth is, I’ve been a vegetarian my whole life. I love animals, nature, trees… Those pigs had an exceptionally good life. Some of them grew to 300 kilos, which is extremely rare—there aren’t even 20 pigs like that in the world. Each one had two hours of tattooing per week, under veterinary supervision, under anesthesia. Afterwards, they’d get a massage, skincare treatment, and as a reward—ice cream.

So pigs eat ice cream?

They love ice cream!

Your “Gothic” series of X-rays of explicit scenes raised many questions about privacy and voyeurism. What was your intention with that work?

All three of the projects you mentioned—Cloaca, the tattooed pigs, and the X-ray images—were created during the same period, a time when I was asking questions about human identity, the body, genetics, and evolution. This was shortly after the cloning of Dolly the sheep, which deeply fascinated me. I began studying Darwin, genetics, DNA. Among these projects, the pigs later became the most controversial due to animal rights concerns. Cloaca was different—it didn’t harm anyone. Everyone defecates—it’s universal and democratic.

The X-ray images had a similar effect—they erase differences between people. I remember one woman who didn’t consider herself beautiful, but when we scanned her body, the radiologist told her: “You have a perfect collarbone, I’ve never seen such symmetry.” That compliment surprised her, because we don’t usually associate beauty with bones, and yet, the beauty was there. Like Cloaca, that project questioned what it means to be human. Do we have to reproduce to be considered human? Do we need to redefine our ideals of beauty and identity? In Florence, you can see Michelangelo’s David, but he no longer represents the modern human being. If we were to choose an image to send into space today to show who we are, it wouldn’t be David. He doesn’t represent human diversity—he represents a white man with a small penis. (laughs)

That’s why, through these projects—Cloaca, the X-rays, the deconstruction of the body and identity—I wanted to create new portraits of humanity. Not classical representations of people, but portraits of post-humanity.

You’ve spoken about your generation of artists, who had to reshape prevailing paradigms. How do you see today’s generation? What should young conceptual artists be doing now? What are they doing?

New things are being created every day, but they no longer share the same universe, the same space with us. I belong to the world of the artwork—a space where we, the older ones, pat each other on the back and tell ourselves there aren’t many creative young people today. But they do exist—only, they don’t live in our world. Their world is TikTok, YouTube, and other social media platforms, where there’s a real explosion of new ideas. They may not call themselves artists, but influencers, content creators, or something else—but they’re using a new language and creating in a different medium.

I would by no means say they’re less creative. On the contrary, they might be more creative than ever before.

How has technology, like artificial intelligence or 3D printing, changed your artistic process? Do you think museums and galleries will always be the best places to present art, or will art move into the digital world as well?

I don’t know. I’m happy doing what I do, but I see how much the world has changed. Fifteen years ago, I bought an old castle with a large piece of land, wanting to create a sculpture park there. But I quickly realized how impossible that was. The authorities buried me in bureaucracy—building permits, zoning plans, cultural heritage regulations. People would come and tell me, “You can’t use that plaster, you have to use this other one.” And I wasn’t trying to build a cathedral—just a small sculpture garden! After years of struggle, I simply gave up.

That’s why I’m now fascinated by the metaverse—a space without bureaucracy, without material constraints, where you can build anything instantly. But I’m still waiting. Being the first in something is always expensive—and often pointless. The first inventor of the car might have invented the vehicle, but there still weren’t good roads. It’s the same with today’s metaverses—there are many of them, but none are quite good enough yet. Everything looks artificial, lacking real detail. It seems like they’re full of visitors, but most are just inactive accounts that haven’t been turned off.

On the other hand, artificial intelligence has already changed the way I work. A job that used to take me two years, I can now finish in a month. But that raises an important question: if something becomes too easy, does it still have value? The first wave of artists who used new technologies often created bad art. Technology doesn’t become obsolete—it matures. The question is how it will evolve. These days, when I’m working on new sculptures, I ask my team: “Can AI do this?” If they say no—it makes me happy.

Maybe I have five or ten more years of work ahead of me. Cloaca was an experience: it smelled, it ate, it groaned—it was a machine that offered an almost religious experience. That’s something AI can’t replicate. If I were a photographer, maybe I’d be worried, maybe I wouldn’t sleep at all. (laughs)

Which of your projects is your favorite?

That’s hard to say because I, too, am influenced by the times, by the spirit of the age—the Zeitgeist. Two years ago, I was almost ashamed of the tattooed pigs. I wondered whether I should even keep them on my website or whether it would be better if everyone just forgot about them. But then I realized—tattooing is just an ancient technology, maybe even older than ceramics. After all, it was a biotech project, a vision of the future in which biotechnology would bring cancer treatments and eliminate disease. But I couldn’t predict the pandemic. Instead of a biotechnological revolution, we got COVID. Instead of progress, we returned to traditional wars.

Everything depends on the spirit of the times, and I try to adapt. Maybe in five years I’ll tell you something completely different. The only constant is Cloaca, but even that isn’t welcome in galleries these days. Gallerists don’t like it because they can’t sell it. They prefer my small bronze sculptures. People like them, people buy them. Art is never just personal—it’s also social. It depends on context, on the public and public opinion, on that same Zeitgeist. Everything is always changing, so maybe next week I’ll have a new favorite…

Is there an idea you had that was too radical to realize—too radical even for you?

Oh, yes! In the late ’90s, I collaborated in Ghent with a crazy curator, Jan Hoet. Okay, he wasn’t exactly crazy, but he was incredibly passionate and colorful. At that time, he was organizing the Sonsbeek exhibition—something like a lesser-known version of Documenta in Germany. My plan for the exhibition was to find a dog with a flat forehead and ask a plastic surgeon to reshape its face to look like mine. I called the project Laika, after the first dog in space—I wanted to create a new historical Laika. I thought the idea was brilliant. By the way, I often test curators by pitching radical projects. If there’s a project I don’t really want to do, instead of saying a direct “no,” I’ll propose something absurd—and when they reject it, the problem is solved.

But when I presented the idea to Jan Hoet, instead of rejecting it, he said: “Why not?” He even offered to connect me with a top plastic surgeon and said he would cover the costs himself. Times were different back then. Today, a curator would probably stop returning your calls—or call the police. (laughs)

But Hoet was thrilled. When I got home, I started testing reactions. I asked colleagues, critics, friends, family, neighbours. The reactions were overwhelmingly negative. People were horrified: “Are you insane? That’s not funny! Why would you even do that?”

People love dogs. We can ask why that dog would be more valuable than a pig or a worm, but the fact is, dogs occupy a special place in human hearts. I realized that even though the idea was provocative, it wasn’t something I truly wanted to carry out. I do have a conscience, after all. (laughs) I called Hoet and told him I was backing out. He was disappointed. He even had a Marxist reading of the whole project: the dog becomes the artist, the bourgeoisie likes to keep a little dog in their lap, the artist as a lapdog of the rich. I was proud of the idea—but I knew I never wanted to make it real.

How do you prefer to spend your free time? What do you do when you’re not making art?

It’s hard for me to answer that because everything in my life is closely tied to art. My attention span can be extremely wide and long-lasting—I’m interested in both modern and ancient art, archaeology, antiques. Compared to some of my peers who are completely focused only on their own field, I’m not so bad. (laughs) I used to be a passionate film lover, but that obsession faded. Art has always been my primary interest. Since a very young age, I’ve never done anything else.

Many artists have stories about working in restaurants, teaching, or doing all sorts of jobs before they became artists. Not me. I’ve never been anything but an artist, and honestly, I don’t even know if I could do anything else. Even if I tried, I doubt I could stay focused on it for long.

How does an artist like you define success? Is it market value, social impact, or something else? How would you like to be remembered in the art world?

That matters much less to me now than it did before. When you’re in your twenties, you’re obsessed with how you’ll be remembered. You read the Iliad and see its heroes willing to risk their lives just to leave a mark on history—probably because they were twenty-something too. But over time, that concern fades. I think it has to do with freedom—if you worry too much about your legacy, you lose spontaneity. Carrying that burden means you can no longer play, explore, or do things just for the joy of it.

When I was younger, there were always expectations. People would stop me on the street, ask for autographs, give me advice about my path. That stifles spontaneity. Today, I no longer need others’ approval—or at least not nearly as much as I used to.

As you get older, you either become a misanthrope or simply more self-assured. I think for me, it’s the latter—I’m not as insecure anymore.